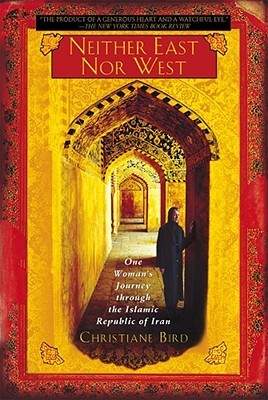

Women smuggling vodka into restaurants in pocketbooks or under chadors? Not the typical CNN-FOX view of Iran, but an inside perspective we could use more of in the West. That’s Christiane Bird’s Neither East nor West: One Woman’s Journey through the Islamic Republic of Iran.

For a link with last week’s entry, let me note that the first chapter begins with a quote from Graham Greene’s Journey Without Maps.

Bird spent several years of her childhood in Iran as the daughter of Presbyterian missionaries in the early 1960s, and made this trip in the late 1990s, after the election of the relatively moderate president Khatami, which made it easier for Americans, at least in some numbers, to enter the country. She sought to understand Iran in all its complexity, to fathom the gap between its Muslim and its classical or pre-Muslim identity. The Shah had emphasized the greatness of the ancient empire at the expensive of religion, but priorities switched after 1979. Bird is also desparate to find out how things have changed since her residency and, more importantly, the Revolution—something she asks locals frequently, receiving various answers.

One of the most obvious differences is that the komiteh, or morality police, run around giving warnings and citations for women who expose too much hair or wear too much makeup. The hijab in Iran typically ranges from the chador, a body-length semicircular cloak tossed over the head and held together by hand, to the rusari, or scarf, often accompanying a manteau. (For specifics see this link.) Still, laws are stricter in some other Muslim countries; consider that in Saudi Arabia women aren’t even allowed to drive.

People always find detours around such restrictions, especially in large cities. She learns of imams who deal in “temporary marriage,” usually a thinly vailed form of prostitution, and of both setbacks and advances in women’s rights since the Revolution; such as the fact that a man can no longer unilaterally divorce his wife. One of Bird’s companions points out a café where friends used to hang out until the manager started reporting illicit meetings of couples to the komiteh. At a party in a wealthier North Teheran neighborhood, the rusari and manteaux come off, discussions of religious skepticism ensue, and the booze comes out.

In the Islamic Republic, Christians are allowed to consume alcohol – and produce it. That’s where the Armenians come in. Other ethnicities Bird encounters include Zoroastrians, who, as “people of the book” along with Jews and Christians, are a tolerated religion, as well as Azeri in the northwest and Turkmen in the northeast.

She visits a martyrs’ cemetery and sees the poignant commemorations family members hold for young males lost to the Iran-Iraq war. She adjusts to the schedules of sleeping, eating, waking and napping: businesses typically close “between 1 and 5 P.M., before reopening again until 10 or 11.” On a trip to the holy shrine of Hazrat-e Masumeh, as a Westerner and non-Muslim, she can only get in by disguising herself under a chador among throngs of pilgrims.

But her most adventurous outing is to the Valley of the Assassins, her attempt to retrace the footsteps of Freya Stark, whose Winter in Arabia I’ve written about here. She can’t visit all the villages Stark did—some have disappeared, or maps are inaccurate—but she manages to see and climb a good deal of the mountainous landscape. She argues with her guide over a host of issues, including whether she can remove her rusari partway through a long, hot hike – after all, no one else is around, so it’s not like they’re “in public.” She also gets a simple village woman’s answer on what the revolution has brought: electricity, a road, a phone.

Bird covers the geographic variety of the country, the interactions of the poor and the elite, the religious and the secular, and she lays open the legalistic, the illicit, and the constant testing of boundaries in Iran. Fifteen years since its publication, it is still valuable reading for anyone wishing to understand this complex society beyond typical media tropes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed