|

Crime and Punishment, the great psychological novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky, first appeared in serial form in 1866. For this anniversary, let me just note as an example of the author's brilliance that the central character, Raskolnikov, has become an archetype of criminal psychology. For more insight, please see this article by a former professor of mine at Ohio State, Dr. Angela Brintlinger.

1 Comment

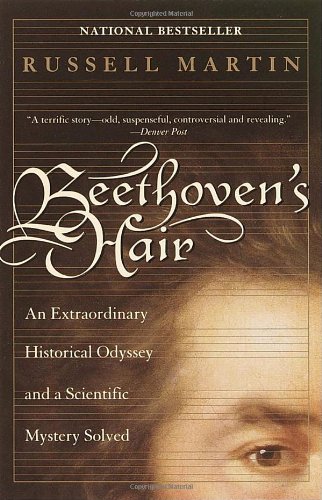

Beethoven’s Hair, by Russel Martin, Broadway Books, 2000 (276 pp.)

This week I’m briefly reviewing a book that is not travel writing per se, but does weave remarkable stories of Beethoven’s life – and his death in my favorite musical city, Vienna – with the mysterious journey of a lock of his hair to Denmark at the end of World War II. The book starts with the opening of a locket of hair at the University of Arizona Medical Center in Tucson, then alternates between vignettes from the composer’s bio and the modern search for the origin of the locket. The hair, it turns out, was snipped from Beethoven’s head as his body lay in repose. The “guilty” party: a young musician named Ferdinand Hiller, son of a merchant who’d changed his surname from Hildesheim to conceal his Jewish identity. The Danish town of Gillileje, where the hair turned up in the 1990s, had been the scene of a rescue of Jews at the end of the war, part of a nationwide effort. Denmark had surrendered to Germany early on, essentially without a shot, and had then been subject to a lenient occupation. At war’s close, the losing Nazis attempted to carry out as much of the “Final Solution” as possible, rounding up Danish Jews and those from other parts of Europe who had found a relatively safe haven there. The Danes, rare for occupied lands at the time, considered it a patriotic duty to protect their Jewish population. As a testament to this fact alone, the book is worth reading. It’s also worthwhile for the Beethoven biography, even though it might make his fans uncomfortable: the curmudgeonly artist did nearly everything possible to sabotage his relations with friends, relatives, and patrons. Somewhat excusable, however, given his many ailments—and the terrible medical advice he received on treating them. One can’t help feel sympathy for the man when reading how he was so distraught over his hearing loss that he considered suicide as early as 1802 (living in the Vienna suburb of Heiligenstadt, which I have visited). Yet he dedicated himself to his art for another quarter-century, leaving us with, among other works, his glorious Ninth Symphony. I’ll wind up to avoid too many spoilers, but I will remark that the book ends on a positive note about a doctor, “Che” Guevara, who cared enough about the musical genius’s legend to pursue research into the causes of his death, and Ira Brilliant, who furthered those endeavors financially and established San José State University’s Beethoven Center. Next week: A Slovak Jewel Well off the Tourist Map Last week I gave my impressions of Freya Stark’s Winter in Arabia; this week it’s Rebecca West’s classic travel book Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey through Yugoslavia.

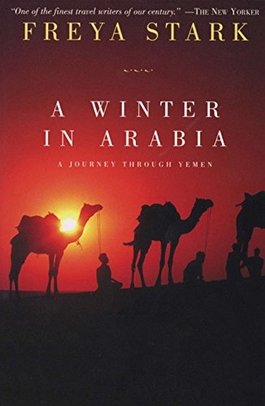

West lacks Stark’s adventurousness – she journeys by car rather than camel, after all – but she makes up for it with encyclopedic knowledge and acute cultural observation. This tome – part journal, part history – stands at 1150 pages plus bibliography and index. I must confess I haven’t read it all the way through, but I still refer to it often. I read a good portion of it as background in advance of my last trip to the former Yugoslavia—which for me was really a visit to the former Austria-Hungary. It was valuable, though by no means perfect. When I mentioned it to a young man in Zagreb, he responded that West was pro-Serb. She certainly had anti-Catholic leanings, typical of those favoring Eastern Orthodox Belgrade. She was also very condemning of the Habsburgs, claiming that the rulers played their constituent nationalities off against each other, for instance, granting privileges to one in order to evoke the envy of another. But she never seemed to produce any positive proof of this motivation. Still, she could be nuanced enough. At the beginning of her “Zagreb VII” chapter, she introduces Bishop Strossmayer, a towering figure of Croat history, through his statue in the public gardens. I found this sculpture, “slim and long-limbed” as West describes it, not far from the rail station, in an open area where local youth had set up a stage and booths for summer evening celebrations. Before that, on my way from southern Hungary to Sarajevo, my driver had stopped the van for supper at a McDonalds in the center of Osijek. On the façade of a building across the street was a plaque honoring Strossmayer, a native of that northern Croatian town. And I’d had the advantage of learning from Black Lamb and Grey Falcon just who he was: a late nineteen- and early twentieth-century Austrian who spent considerable personal wealth helping the Croat nation develop and preserve its cultural and literary heritage. He founded the University of Zagreb, didn’t favor Croats over Serbs and was, in West’s view, a “fearless denunciator of Austro-Hungarian tyranny.” Exemplary of his liberal spirit, West, says, he was one of only four clerics to vote against the declaration of papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council. As I travelled around the norther Dalmatian coast, I could see what she'd meant about the bleak landscape – well the shore is beautiful, but the hills above, quite bare – being despoiled when, centuries ago, the filthy-rich Venetian Republic “cut down what was left of the Dalmatian forests to get timbers for their fleet and piles for their palaces.” As in so many instances, West’s remark is on the button. Her magnum opus is also peopled with the lively characters she and her husband meet, such as Constantine and Valetta, a Serb and Croat who constantly argue over culture and politics. Many of her observations are on the mark, although they might appear to some modern readers as cheap stereotypes. The Slavs never have enough of a good thing, she says of their propensity to eat enormous quantities of food—and expect their guests to do the same. Anyone who has lived among Slavs can attest to this tendency. While I don’t agree with all Rebecca West’s interpretations of history, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is indispensable for anyone wanting to acquire a deep and broad knowledge of the region before travelling there. Written after her journey of 1937, it serves partly as a warning of things to come. Her prescience extended not just to WWII, but also to the civil wars of the 1990s. As one reviewer commented on the book’s Amazon page, “Love it or hate it, anyone with an interest in the Balkans will eventually have to deal with this book.”  I’ve been promising to finish out my “What I Read Last Summer” series with two books, both from the late 1930s to early 1940s, a time when female travel writers were, to say the least, a bit audacious. Here’s the first, Winter in Arabia, by Freya Stark (1940) I first learned of Stark’s travels from Neither East Nor West, Christiane Bird’s account of her own extended visit to 1990s Iran. The title is an allusion to Stark’s 1945 East is West, based on her wartime experience with the British Ministry of Information in Arabia. Stark’s travels in the Middle East had begun in 1927 with her first visit to Lebanon, and by 1931 she had traveled three times to Iran, to parts previously unexplored by Westerners, including men. Most famously, she pinned down the location of the storied Valleys of the Assassins. (The English word comes from the Arabic hashishiyyin, or a similar Farsi word for “hashish eaters,” as the fabled killers would commit their acts after intoxicating themselves). Winter in Arabia describes in very humanizing detail her 1937-38 expedition to what is now Yemen. She traveled with a female archeologist and another woman. Stark’s attitude towards the locals is enlightened for the time: We are in a proud country still new to Europeans, the first foreigners to live in its outlying districts for any length of time; and the hope that I cherish is that we may leave it uncorrupted, its charm of independence intact. I think there is no way to do this and to keep alive the Arab’s happiness in his won virtues except to live his life in certain measure. One may differ in material ways; one may sit on chairs and use forks and gramophones; but on no account dare one put before these people, so easily beguiled, a set of values different from their own. Discontent with their standards is the first step in the degradation of the East. And she does live their life, as reflected in this passage about two of her hosts, and a situation in which jewelry has disappeared: [The presumed thief] appeared, dressed for the feast, with finger-joints and palms yellow with henna and festal ringlets round her wizened old face…. She had taken no rings, she said. ‘Well, then,’ said Qasim, ‘you will have to drink the talisman that the sayyid has prepared for you, and if you are speaking the truth nothing will happen, but if you took the rings you will swell out like this’—he made a balloon-like gesture in front of his own slim tummy. The floodgates of eloquence were now loosened. She stood with upraised hands, her rust-coloured dress and blue cloak draped about her like some Mater Dolorosa of a rather florid period, her voice rising in squeaks equally inspired by injured innocence and the prospect of drinking the sayyid’s charm. ‘It can’t do you any harm,’ I said at last. ‘It is words of the Quran, and they only harm the wicked. I will drink too, so that you may not fear.’ Stark’s writing has much the tone of her contemporary Graham Greene in his travel writings, much of it obviously taken from diary. But her descriptions are more vivid. And she went everywhere the bravest Western men went, and beyond, into the world of women, so closed to these male explorers. As travel writer Bill Bryson once remarked, “A Martian coming to earth would unhesitatingly land at Vienna, thinking it the capital of the planet,” thanks to all the imposing architecture of the old Habsburg Empire.

But capital of the Galactic Empire? The thought occurred to me while watching the Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s concert on PBS (viewable here). Host Julie Andrews, about a quarter hour into the broadcast notes that Franz Joseph reigned 68 years, five more than Queen Victoria. The images shift to black and white footage of the old monarch’s funeral in 1916, in the middle of World War I. Then Andrews says that Josef Strauss, brother of the Waltz King “expertly captures the fading empire with the ethereal harmonies of his most famous waltz, ‘The Music of the Spheres’.” I thought of planets revolving and orbiting the sun, which orbits the center of the galaxy. If ever there were a parallel human activity, it is couples whirling around a ballroom floor. And nobody does it better than the Viennese. As “Music of the Spheres” continued, the cameras showed close-ups of the Musikverein’s massive chandeliers, each with hundreds of thumbnail-sized pieces of cut glass. Probably from the former crown land of Bohemia. Come to think of it, Johannes Kepler devised his laws of planetary motion in Prague, then the seat of the Empire. How appropriate! Next week: Freya Stark’s Winter in Arabia

Just to wrap up 2015: One of my proudest moments of the year was to play and sing selections from Emmerich Kálmán’s The Gypsy Princess. The operetta premiered a hundred years ago, Nov. 17, 1915. Thanks to the folks at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Onancock, Virginia for inviting me to appear as part of their coffee house to benefit Shore Keepers, a group devoted to environmental sustainability!

It's also the sort of music heard in New Year's galas, so here it is, six weeks after the original performance.

I have friends who have played violin and cimbal (an East-Central European hammer dulcimer) and sung in the opera in Košice, Slovakia’s second largest city, which also marked the centennial. Article in Slovak.

Finally, there’s this heart-warming piece by Conde Naste Traveler on 2015’s best random (well, almost) acts of kindness in the air.

For 2016, I resolve to post every Monday. Look for my take on PBS' New Year celebration from Vienna on 4 January, and pioneering female travel author Freya Stark on the 11th! |

Archives

June 2023

Musical & Literary Wanderings of a Galloping GypsyMark Eliot Nuckols is a travel writer from Silver Beach Virginia who is also a musician and teacher. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed