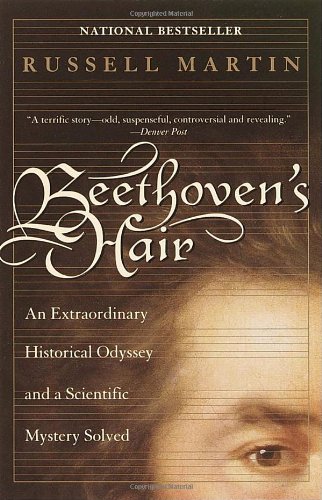

This week I’m briefly reviewing a book that is not travel writing per se, but does weave remarkable stories of Beethoven’s life – and his death in my favorite musical city, Vienna – with the mysterious journey of a lock of his hair to Denmark at the end of World War II.

The book starts with the opening of a locket of hair at the University of Arizona Medical Center in Tucson, then alternates between vignettes from the composer’s bio and the modern search for the origin of the locket. The hair, it turns out, was snipped from Beethoven’s head as his body lay in repose. The “guilty” party: a young musician named Ferdinand Hiller, son of a merchant who’d changed his surname from Hildesheim to conceal his Jewish identity.

The Danish town of Gillileje, where the hair turned up in the 1990s, had been the scene of a rescue of Jews at the end of the war, part of a nationwide effort. Denmark had surrendered to Germany early on, essentially without a shot, and had then been subject to a lenient occupation. At war’s close, the losing Nazis attempted to carry out as much of the “Final Solution” as possible, rounding up Danish Jews and those from other parts of Europe who had found a relatively safe haven there. The Danes, rare for occupied lands at the time, considered it a patriotic duty to protect their Jewish population. As a testament to this fact alone, the book is worth reading.

It’s also worthwhile for the Beethoven biography, even though it might make his fans uncomfortable: the curmudgeonly artist did nearly everything possible to sabotage his relations with friends, relatives, and patrons. Somewhat excusable, however, given his many ailments—and the terrible medical advice he received on treating them. One can’t help feel sympathy for the man when reading how he was so distraught over his hearing loss that he considered suicide as early as 1802 (living in the Vienna suburb of Heiligenstadt, which I have visited). Yet he dedicated himself to his art for another quarter-century, leaving us with, among other works, his glorious Ninth Symphony.

I’ll wind up to avoid too many spoilers, but I will remark that the book ends on a positive note about a doctor, “Che” Guevara, who cared enough about the musical genius’s legend to pursue research into the causes of his death, and Ira Brilliant, who furthered those endeavors financially and established San José State University’s Beethoven Center.

Next week: A Slovak Jewel Well off the Tourist Map

RSS Feed

RSS Feed