You might know him from the classic film noir The Third Man (1949), set in post-war Vienna, starring Orson Welles among others, and famous for its eerie theme music played on the zither. Greene wrote the screenplay and subsequently published the novella on which it was based. His 1940 The Power and the Glory, about a renegade Mexican priest, was made into 1947’s The Fugitive (dir. John Ford, starring Henry Fonda). And his 1958 Our Man in Havana, a satire on British intelligence, which also anticipates the Cuban Missile Crisis, was adapted into a movie of the same name the following year.

His first non-fiction travel book was Journey Without Maps (1936), a chronicle of his wanderings through the interior of Liberia when that territory was still uncharted – hence the title. His unprejudiced and sympathetic view of the locals, and his acute observations are remarkable for the time. It bares comparison to Freya Stark’s Winter in Arabia (which I have reviewed here), though I found Stark’s vivid and insightful prose a bit superior.

But Ms. Stark had already spent considerable time in the Mid-East at that point, and Greene’s trip to Africa was only his first abroad. Of course, it was only the beginning, as he was recruited into MI6, and later spent time in Mexico, Cuba, Haiti, and elsewhere. His sympathy with the downtrodden is reflected in his frequent choice of poor, hot countries as backdrops, often dubbed “Greeneland.”

Prosperous Switzerland, where Greene died in 1991, is the setting for his excoriation of greed, Doctor Fischer of Geneva or the Bomb Party (1980). The central character’s title is of dubious origin, as is that of his toady “General” Krueger; other associates, who attend his frequent parties, include M. Belmont, who’ll “solve any tax problem.” Fischer is so cruel he publishes a comic making fun of a disabled member of his entourage, Mr. Kips.

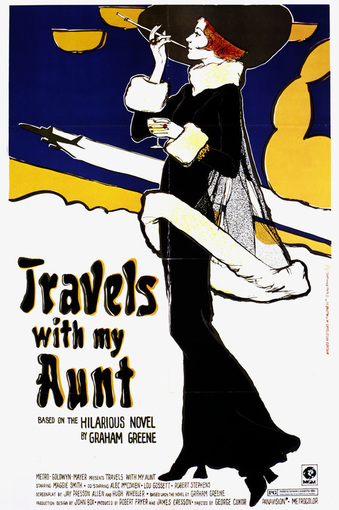

Greene’s satire is typically bolstered by clever use of narrative voice. Travels with my Aunt (1969, made into a 1972 movie) is told by a single, middle-aged naif, Henry Pulling, whose aunt takes him under her wing after the death of his mother. He soon embarks on eye-opening travels around Europe with the shrewd and worldly old lady. His gradual awareness that she is involved in crime, his first marijuana experience on a train to Istanbul, and other misadventures unfold in a manner that masterfully keep readers engaged and entertained. He, his aunt, and another character I’ll not disclose to avoid spoilers, end up in Paraguay. Great armchair travel.

I just finished The Quiet American (1955), about a U.S. operative in Vietnam back when the French were struggling against the communists. His title character, Pyle, who has just showed up in the country, insists that what the Vietnamese need is a “Third Force,” tainted with neither communism nor colonialism. His conviction rests solely on books by an American professor who himself never spent more than a week in the country. Despite Pyle’s naiveté and idealism, he soon gets himself involved in sinister dealings that may be his undoing. Prophetic stuff.

First-person character Fowler is older, cynical, and more perceptive by contrast. The story is driven largely by the odd rivalry that develops when Pyle unabashedly steals Fowler’s young Asian mistress, but the two remain friends. They’re nearly killed together one night after being trapped in a watchtower on the way back home to Saigon from an outlying town.

Despite his knowledge and wisdom, Fowler is an “unreliable narrator”: he smokes opium daily, admits that he’s not being honest in his correspondence with his estranged wife back in England. He at least questions his motivations, never claims to have much character or principles. And he clearly is attuned to the sufferings of the local population.

I have to re-read this one – I’m sure there’s lots of subtleties that didn’t catch my attention the first time around. Anyway, if you haven’t sampled Graham Greene yet, I hope I’ve piqued your curiosity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed