The novel begins when Ellis Hock’s wife deserts him, and he leaves his family’s menswear business to return to Malawi, where he’d served in the Peace Corps. Once there, he finds the school he helped build is run down, and the country is full of corruption.

I can identify with this nostalgia for a foreign stomping ground from younger days. I feel much the same attachment to Central Europe, especially Slovakia. The difference between Hock and me, though, is that I’ve kept in touch with Slovak friends and have revisited every couple of years.

And so I’ve not been quite as shocked. True, reforms that began just after the East Bloc’s dissolution haven’t panned out as I’d hoped: there have been far more winners than losers in the new economy, NATO membership has been as much about arms contracts as anything else. But there have been improvements in health, hygiene, safety, service with a smile, more open and questioning attitudes in education. English is now widely spoken, at least among under-forties, and I did my share as a language teacher (in part for the Soros Foundations).

But Slovakia is not Malawi, where Theroux spent his Peace Corps years. Back in 2005, the writer had lambasted the corrupting influence of Western aid—and the patronizing assumptions underlying it—in a New York Times op-ed called “The Rock Star’s Burden.” The Lower River represents an expansion of that critique into novel form.

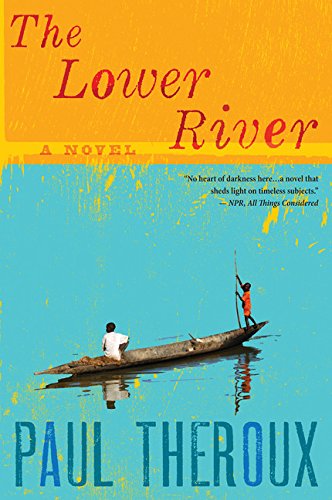

It takes the reader through constant plot twists and unexpected developments, including Ellis Hock’s virtual entrapment in his old Malawian village. It makes masterful use of images, such as the snakes that keep appearing. Hock is a man who knows how to handle them in a place where they are deeply feared. But this is one of this flawed character's few strengths.

The character's weaknesses, his utter helplessness in the end, help make The Lower River the eye-opening, earthy thriller that it is.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed